Evidence Of Afterlife - Hyperthymesia

Evidence: If certain individuals among us can remember past moments with intricate and detailed clarity, then it is evidence that memory holds immense, hidden capacity for all of us

Evidence Confirmation - Hyperthymesia

1. What Specific Evidence Are We Looking For?

1.1. Memory Assertions Made by Proof of Afterlife

The six theories that makeup "Proof of Afterlife" contain assumptions that are not accepted by the scientific community, nor by the public in general. We assert these assumptions to be true because the mathematics of afterlife dictate it to be so. A large factor in afterlife is memory. Memory plays a critical role in enabling conscious awareness to exist after life concludes. Here are the specific aspects of memory that we assert as true. The fact that our assumptions are not generally accepted by the public does not necessarily mean they are not true. In this evidence case by hyperthymesia, we intend to show that certain people have what has been called super memory, demonstrating that such a thing does exist, although it is extremely rare.

1.2. One: That Memory is All Inclusive. It Absorbs the Surrounding Environment in Total, Always

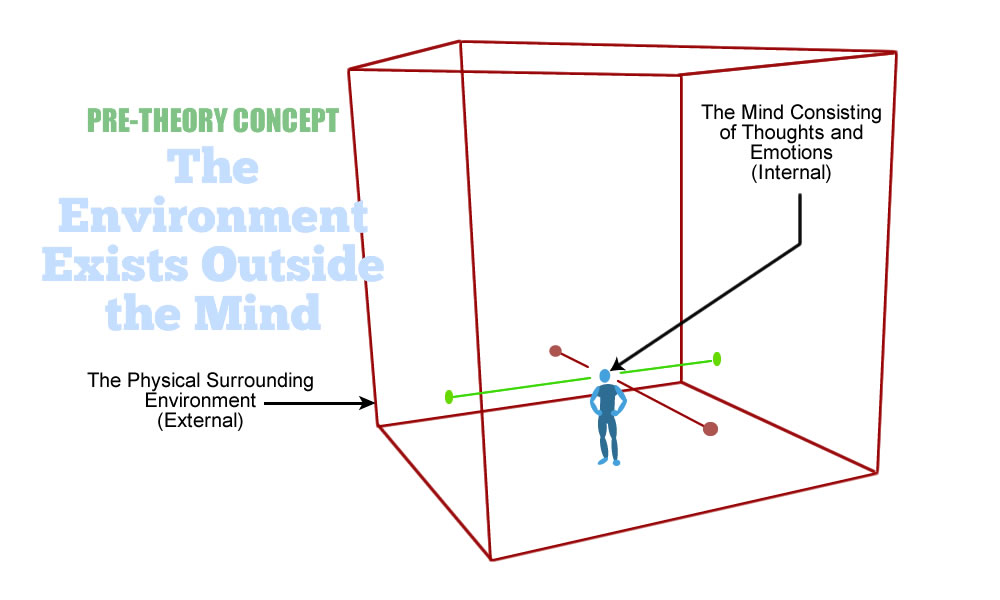

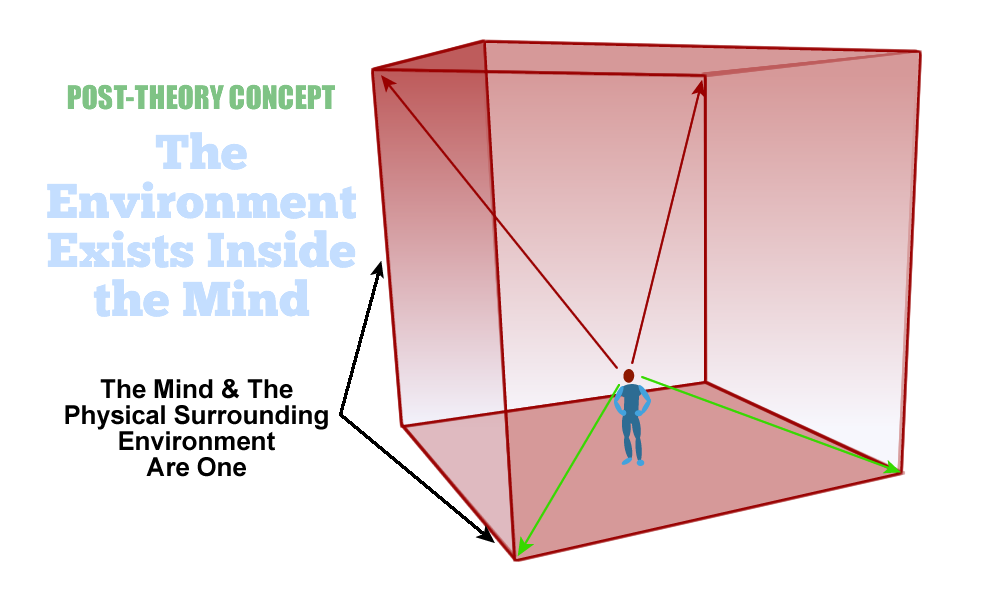

What the consensus believes: The consensus sees the surrounding environment as taking place on the outside - external to one's self. They tend to see the world as exterior to themselves. They think of their thoughts and emotions as being inside their mind. However, they see the surrounding world as being outside their mind. The world believes these are two separate entities.

What the theory believes: The theory believes that the outside world is manifested within the mind. The stimulus comes in through the senses and moves into the mind, where it is assembled into the "world" inside the visual cortex. Under this mode of understanding, the world is first "realized" inside the visual cortex where it is already inside the mind. There is no "out there" using this approach. We regard the mind generally, and the visual cortex specifically, to be memory. So we believe that the outside world is actually inside memory.

1.3. Two: That Memory Does Not Forget - It Drops No Bits.

What the consensus believes: The consensus is that human memory is inherently flawed. This view is brought about by equating what we can remember versus what is in memory. We think that if we can't remember what we had for lunch yesterday, the memory of it has faded from view, is lost, and can never be recovered.

What the theory believes: The theory draws no parallel with remembering versus memory. On the contrary, we believe that memory is intact. However, our ability to recall it is fallible. We believe that memory is captured as life unfolds and it remains intact, exactly as it happened the first time. We believe remembering and memory as two completely different things. Our ability to remember has no bearing on what is in memory. Human memory, like computer memory, does not drop bits. It is infallible. However, our ability to remember things is limited.

1.4. Three: All People Are Endowed with Super Memory, Not Just the Hyperthymesic.

What the consensus believes: As you will see, hyperthymesia is a condition where certain people can remember past moments with incredible detail. Most people believe these people have larger memories than we do. They believe that hyperthymesia individuals have more memory capacity than the rest of us.

What the theory believes: The theory believes that hyperthymesic people have immense, perfect memories. We also believe that everyone has an immense perfect memory. What differentiates them from us is they have a heightened ability to remember. It is not that their memory is larger. It is their remembering ability that is larger. Both they and the rest of us have the same perfect memory.

2. Hyperthymesia: The Rare Phenomenon of Super Memory

2.1. What Is Hyperthymesia?

Hyperthymesia is the uncommon ability that allows a person to spontaneously recall with great accuracy and detail a vast number of personal events or experiences and their associated dates.[1]

Hyperthymesia is a rare neurological condition where individuals possess an extraordinary ability to recall events from their lives with remarkable precision. These individuals can remember dates, events, and even seemingly trivial details from their past with accuracy that far exceeds the norm. While this phenomenon has been the subject of fascination in scientific and public circles, it raises intriguing questions about the nature of memory, its neurological basis, and the implications of such exceptional recall.

2.2 What Are the Characteristics of Hyperthymesia?

Hyperthymesia is characterized by an individual's ability to recall personal experiences and life events with remarkable clarity. Unlike eidetic memory, which pertains to the retention of visual images, hyperthymesia primarily concerns episodic memory - the recall of specific experiences in time. These memories are often vivid, involuntary, and emotionally detailed, allowing individuals to mentally relive past moments.

Hyperthymesia involves an exceptional ability to recall autobiographical events. Individuals with this condition can remember specific dates, emotions, and contexts with striking clarity. Despite their exceptional autobiographical recall, individuals with hyperthymesia do not necessarily excel in other memory tasks, such as memorizing random information or learning new material.[2] This specificity suggests that hyperthymesia is not a generalized memory enhancement but a unique condition involving personal experiences.

2.3. How Prevalent Is Hyperthymesia?

The prevalence of hyperthymesia is remarkably low. Since the initial case study of Jill Price in 2006, fewer than 100 individuals worldwide have been identified with this ability.[3] Several factors contribute to this rarity and the difficulty in determining its true prevalence:

Diagnostic Challenges: Testing for hyperthymesia requires rigorous verification of memory accuracy over a wide range of life events, often relying on diaries, calendars, and corroborative evidence. Such testing is time-intensive and costly, limiting widespread screening efforts.[4]

Underreporting: In some cases, individuals with hyperthymesia may not recognize their memory abilities as extraordinary, especially if they have no frame of reference for comparison. This underreporting may lead to an underestimation of its prevalence.

Cultural and Social Factors: Cultural norms and societal emphasis on autobiographical memory may influence the identification of hyperthymesia. In societies where detailed personal recollection is less valued, individuals with the condition may go unnoticed.[5]

The rarity of hyperthymesia can also be attributed to its neurological underpinnings. Studies show that individuals with hyperthymesia often have structural and functional differences in brain regions associated with memory, such as the amygdala and hippocampus.[6] Enhanced connectivity between these regions may facilitate the vivid recall of personal experiences. However, these neural characteristics are not commonly found in the general population, explaining the condition's scarcity.

Hyperthymesia remains an exceptionally rare phenomenon, with fewer than 100 documented cases globally. The rarity of this condition underscores the uniqueness of its neurological and genetic basis while highlighting the challenges of its identification and study. Despite these challenges, hyperthymesia provides a valuable lens through which to explore the complexities of human memory, offering insights into both the extraordinary potential and natural limitations of our cognitive systems.

This rare condition also known as highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM) causes people to remember just about everything that has occurred in their life. This includes every conversation and emotion ever experienced as well as every person encountered, regardless of how insignificant or minute. It appears there are fewer than 100 people who have the condition out of eight billion people on earth. This means that one person out of one hundred million people can remember events from most days of their lives. Admittedly this isn't a large sample size, but that's not the point. The point is that supermemory exists. It exists in the background, waiting to be drawn upon. It can be thought of as a huge, untapped reservoir.

2.4 Hyperthymesia and the Quality of Memory in All Humans

Hyperthymesia offers a unique perspective on the quality of memory in humans by revealing the extraordinary potential some individuals have to recall personal experiences with vivid detail and accuracy. While individuals with hyperthymesia can effortlessly remember specific events, dates, and emotions from their past, the majority of people do not have such abilities. This highlights the variability in memory capacity across individuals, suggesting that while all humans possess an immense potential for memory storage, the quality of recall varies widely. For most people, memory is a dynamic process that prioritizes relevant information, filtering out less pertinent details to prevent cognitive overload. In contrast, hyperthymesia allows for the retention and recall of extensive autobiographical data, which may offer both benefits, such as enhanced life experiences, and challenges, like emotional overload. Overall, hyperthymesia underscores the complexity and diversity of memory, illustrating how individual differences shape our ability to access and experience our pasts.

3. Three Accounts of People with Hyperthymesia

3.1. The Intention and Interpretation of Using Real-Life Accounts

We have included three real-life examples of Hyperthymesia - Brad, Jill, and Bob. What we are intending to do is show practical examples of superior memory. All three individuals can recall numerous specific details about any random day that exists in their past. With these accounts, we are intending to provide evidence for the vast potential of human memory. It is not that this capability is within them, it is this capability is within us all. You can find further information on the case in the footnotes and bibliography below.

When reading these accounts, pay attention to the similarities between them. We are attempting to show a memory capability. One of the major tenets of Proof of Afterlife is that the mind captures the present moment into memory, totally and perfectly. We take it a step further by saying that the present moment is already in memory at the moment we experience it. That means that the present exists within memory - all moments - for everyone.

These individuals with hyperthymesia can look back into these moments that exist within us all. Thus, their accounts support the tenet that the mind captures the moment entirely and then stores it in memory indefinitely. The hyperthymic memory provides proof that these memories do exist, exactly as predicted. The three accounts are strikingly similar in their ability to look back and access moments that exist in memory.

3.2. Brad Doe, the "Human Google"

The Story of Brad Doe

One of the most notable cases of hyperthymesia is that of Brad Doe (a pseudonym to protect the individual), an American journalist who has demonstrated an incredible ability to remember daily events spanning decades. Brad's unique memory capabilities were first noticed by his family and colleagues, who observed that he could recall precise details of past events without prior preparation.[7] His case gained public attention when his brother documented his abilities in a film titled Unforgettable (2010), which showcased the breadth and accuracy of his recall.[8]

Brad's memory was extensively tested by cognitive researchers, who found that he could accurately recall dates, weather conditions, and even minor news events from years past. Unlike individuals with photographic memory, who retain visual details with high precision, Brad's ability is specific to autobiographical and factual recall.[9]

Brad's Extraordinary Memory Feats

Brad Doe, often referred to as the "Human Google," is an American with an extraordinary memory, known as hyperthymesia - a condition that allows him to recall an exceptional amount of personal and public historical events with extreme accuracy. One of his most well-documented memory feats was demonstrated in media interviews, where he was asked to recall specific events from random dates in history.

In one such demonstration, Doe was challenged to recall details from a random date provided by an interviewer. When given a date such as March 3, 1985, he could immediately identify the day of the week, recall major news headlines, and even mention personal details about his activities on that day[10]. His recall was later fact-checked against historical records and found to be strikingly accurate.

Brad's ability has been studied by researchers investigating "autobiographical memory", a rare cognitive phenomenon that allows individuals to recall past experiences in vivid detail[11]. Unlike ordinary memory, which relies on reconstruction, Brad's memory operates with near-total recall, making him one of the few known cases of hyperthymesia.

His feats have been featured in various documentaries and media outlets, where he has consistently demonstrated an ability to recall events, sports scores, and even daily weather patterns from decades past[12].

3.3. Jill Doe, A Case of Highly Superior Memory

The Story of Jill Doe

One of the most well-documented cases of hyperthymesia is that of Jill Doe (a pseudonym to protect the individual), an American woman whose case was first studied in depth by neuroscientists in the early 2000s. Jill Doe first contacted researchers at the University of California, Irvine, in 2000, describing her unusual memory abilities.[13] She claimed that she could recall, in precise detail, events from nearly every day of her life since childhood. Her ability was tested extensively by Dr. James McGaugh and his colleagues, who conducted a series of structured interviews and memory recall tests to assess the extent of her abilities.[14]

While most individuals struggle with recalling specific details of past experiences, Jill Doe possesses a remarkable ability to remember nearly every event of her life in vivid detail. Doe, the first documented case of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM), has been studied extensively by neuroscientists seeking to understand the mechanisms underlying her extraordinary recall.

The Memory Feats of Jill Doe

Jill Doe first gained public attention in 2006 when she was studied by Dr. James McGaugh and his research team at the University of California, Irvine[15] Doe demonstrated an uncanny ability to recall specific details about personal and historical events. When given a random date, she could instantly identify the day of the week, recall major news events, and even provide details about what she was doing on that particular day[16]. For instance, when asked about August 16, 1977, she immediately recognized it as the date of Elvis Presley's death, recalling not only the event itself but also what she was doing when she heard the news[17].

Her memory was later tested against historical records and journal entries she had kept throughout her life, confirming that her recollections were extraordinarily accurate. Unlike individuals with photographic memory, who can recall visual images with great clarity, Jill's memory is highly specific to autobiographical events, making her a rare case in cognitive psychology[18]

Unlike individuals with typical memory function, Jill does not use mnemonic techniques or deliberate memorization strategies. Instead, memories appear to be automatically stored and retrieved, often in response to specific triggers, such as hearing a date or event mentioned in conversation6. However, this ability has also been a source of distress for Doe, as she describes being unable to forget painful or negative memories, experiencing them with the same emotional intensity as when they first occurred[19]. Jill's case remains one of the most fascinating discoveries in cognitive neuroscience. Her ability to recall autobiographical details with near-perfect accuracy has provided a deeper understanding of memory function.

3.3. Bob Doe, A Case of Superior Autobiographical Memory

Memory is an essential cognitive function that enables individuals to recall past experiences, retain knowledge, and navigate daily life. While most people struggle to remember specific details from their past, Bob Doe (a pseudonym to protect the individual) is one of a handful of individuals with Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM), a rare condition that allows him to recall nearly every event from his life with remarkable accuracy. His memory abilities have been extensively documented in scientific research and media appearances, offering valuable insights into the nature of human memory.

The Story of Bob Doe

Bob's extraordinary memory was first recognized by researchers at the University of California, Irvine, where neuroscientists James McGaugh and his team were studying individuals with HSAM. Doe was one of the first few documented cases of this condition and quickly became a subject of interest due to his ability to recall events spanning decades with pinpoint accuracy.[20]

Unlike most people, who rely on notes or diaries to keep track of past experiences, Bob can effortlessly retrieve specific dates, conversations, and historical events from his life. For example, if asked about a random day from the 1970s, he can immediately recall not only what he was doing but also details such as the weather, the television programs that aired, and significant news events.[21]

Demonstrations of Memory Feats

Bob's memory feats have been featured in various media programs, including the CBS News program 60 Minutes and the documentary Unforgettable, where he demonstrated his ability to recall precise details from past decades. When given a date, he could instantly identify the day of the week, recount personal memories, and recall historical events that occurred on that same date.[22]

For instance, in an interview, Doe was asked about December 27, 1979, and he immediately recalled watching a college football bowl game and described the outcome in detail. Fact-checkers verified his claims, confirming the accuracy of his recall.[23]. His ability has led to him being referred to as the "human calendar" by friends and researchers alike. Unlike individuals who use mnemonic techniques to improve memory, Doe's memory is automatic and involuntary, meaning he does not deliberately try to remember past events- they simply resurface when triggered by external cues.[24] While possessing an exceptional memory may seem advantageous, it also comes with challenges. Bob has spoken about the emotional burden of remembering painful experiences in vivid detail. Despite these challenges, Doe sees his memory as a gift and enjoys using it to entertain and educate others. He has even stated that he often impresses friends by reminding them of things they have long forgotten, making him a popular figure in social circles.[25]

Bob's Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory remains one of the most fascinating cases in neuroscience. His ability to recall decades of personal and historical events with incredible precision has not only amazed researchers but has also contributed to a greater understanding of memory mechanisms. His case remains an essential part of ongoing research into human cognition, memory storage, and retrieval.

4. Memory Versus Remembering - A Visual Perspective

4.1. A Visual Representation of Normal Memory

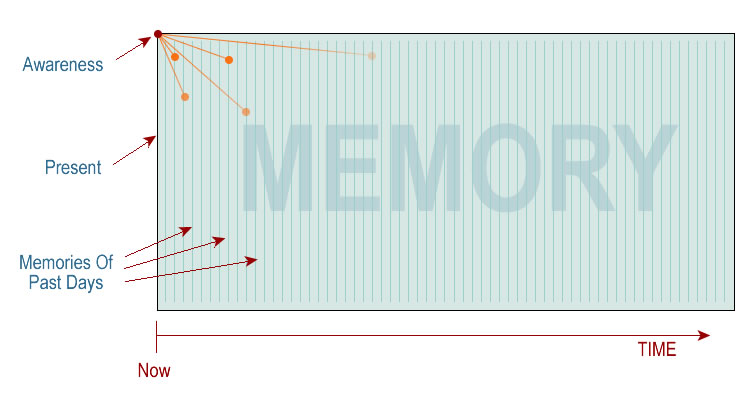

To explain how Hyperthymestic Syndrome works and how it supports the theory of afterlife, look at this diagram. This is a depiction of normal memory. The large box represents memory - the experiences of a person throughout a lifetime. The red dot (in the upper left corner) represents awareness. The left leading edge represents the present.

The orange lines and dots represent the average person's ability to remember. For example, the second orange dot (from the left) represents remembering an event that happened three days ago. Notice how the memory of events fades (isn't as clear) as you get further away from the present.

4.2.A Visual Representation Hyperthymestic Memory

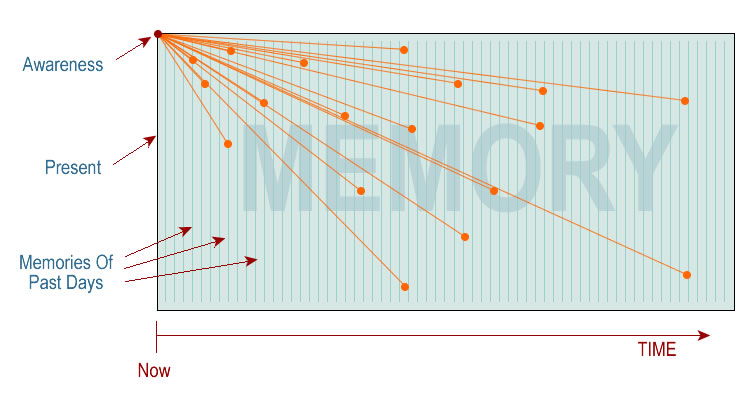

Compare a normal person's memory with the diagram of a person with Hyperthymestic Memory below. Notice how much more memory awareness can be accessed. They can access more events and access them. Hyperthymestic Syndrome is an enhanced ability to look back into memory at moments of the past. The person with this condition can access memory more easily and more completely than the rest of us.

Notice that in both cases (normal and Hyperthymestic Memory) the size of memory and the size of awareness are the same. The difference between the two is the enhanced ability to remember. The reason Hyperthymestic Syndrome serves as evidence of proof of afterlife is because it provides testimony to the vastness and completeness of memory. In other words, if memory were not complete in every detail, then the Hyperthymestic person would have nothing to remember. Hyperthymic memory provides evidence that the memory is there, that it exists, and it can be accessed at any time.

4.3. Remembering is Limited, Memory is Unlimited

The nature of human memory is a complex and fascinating phenomenon that continues to intrigue researchers, philosophers, and neuroscientists. The theory that "remembering is limited, but memory is unlimited" captures the paradoxical interplay between the brain's vast storage capacity and the constraints of conscious recollection. Here we examine the distinction between the potential boundlessness of memory storage and the selective, finite nature of remembering.

The Unlimited Capacity of Memory

Human memory operates on multiple levels, encompassing sensory, short-term, and long-term storage. The long-term memory system, in particular, appears to have an almost limitless capacity. Studies suggest that the brain can store a vast amount of information over a lifetime, far exceeding the capacity of any artificial storage system known today. For example, researchers have estimated that the human brain's memory capacity may be comparable to several petabytes of digital storage - equivalent to millions of gigabytes. This capacity arises from the brain's highly efficient neural networks, which encode and interconnect information in ways that allow for dynamic, multi-faceted storage[26]. The brain's ability to consolidate and retain these memories over decades supports the notion that memory, as a storage phenomenon, is virtually unlimited.

The Constraints of Remembering

In contrast, the act of remembering - retrieving stored information - is inherently limited. This limitation stems from several factors:

1. Cognitive Load: Human attention and working memory are finite resources. At any given moment, the brain can only process and retrieve a limited amount of information[27].

2. Retrieval Cues: Effective remembering relies on the presence of retrieval cues. Without appropriate triggers, even well-stored memories may remain inaccessible. Forgetting often occurs not because the memory is lost but because the pathway to retrieve it is obscured[28].

3. Interference: Similar or competing memories can interfere with recall. This phenomenon, known as proactive or retroactive interference, highlights the challenges of selectively remembering within a vast memory network.

4. Biological Factors: Neurological conditions, aging, and stress can impede memory retrieval, further emphasizing the limitations of remembering.

Reconciling the Paradox

The dichotomy between unlimited memory and limited remembering reflects the brain's adaptive prioritization mechanisms. Storing vast amounts of information ensures life's data are preserved, while selective retrieval prevents cognitive overload. This prioritization allows humans to focus on relevant and actionable information rather than becoming overwhelmed by an endless deluge of stored data.

Moreover, advances in neuroscience suggest that forgetting is not merely a flaw but a feature of memory systems. Forgetting enables the brain to declutter, prioritize salient memories, and maintain cognitive efficiency. This aligns with the "limited remembering" aspect of the theory and underscores the brain's role in optimizing human cognition.

Understanding the interplay between memory and remembering has profound implications. In education, strategies such as spaced repetition and retrieval practice leverage the brain's storage and retrieval mechanisms to enhance learning outcomes[29]. In technology, artificial intelligence systems inspired by human memory models aim to mimic selective remembering to improve data processing and decision-making. The theory also invites philosophical reflections on identity and consciousness. If memory constitutes a fundamental aspect of selfhood, then the selective nature of remembering shapes not only our knowledge but also our sense of who we are.

Conclusion

The theory that "remembering is limited, but memory is unlimited" captures the intricate dynamics of human cognition. While the brain's capacity to store information is virtually boundless, the act of remembering is constrained by cognitive, contextual, and biological factors. This interplay reflects an adaptive system designed to balance information retention with cognitive efficiency. This favors us with a remembering system that serves us well during our lifetime by not overcomplicating our minds. More importantly, it offers us limitless retention of data throughout our lifetime that will be available to us when life ends.

4.4. Super Memory and the Scale of Forgetfulness

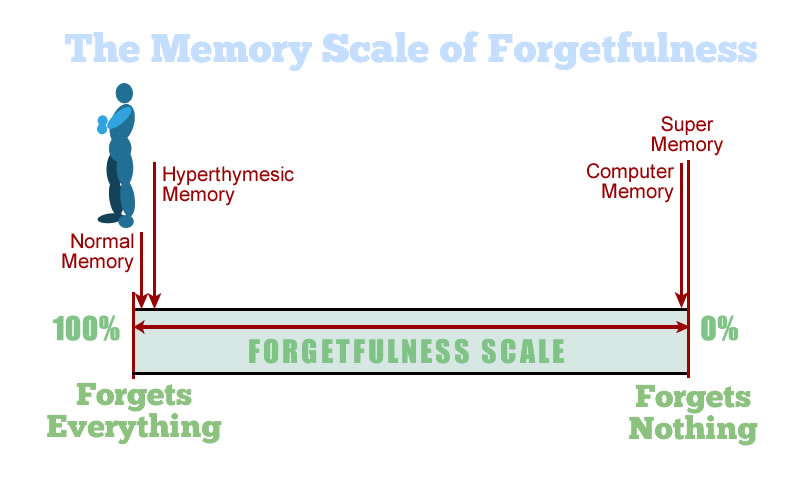

To gain a visual understanding of remembering, memory, and hyperthymesia, I created this illustration. We are going to create a spectrum of forgetfulness. On the left side of the spectrum of memory, we have a memory that forgets everything. In other words, data comes in from the senses, gets stored in memory, and then drops out almost immediately. Memory on this side of the spectrum has no staying power. It has amnesia. Whatever is put into it, drops out immediately.

On the right side of the spectrum, we have memory that retains everything. Whatever data is put into this memory stays there forever. Data goes in and never comes out. Data remains in memory forever. It has the ultimate staying power.

On this scale of forgetfulness, I have placed normal human memory. Notice that it is located almost all the way to the left, just inside total forgetfulness. At this point along the scale, we remember a few things but forget almost everything else.

Notice that I have placed hyperthymesia memory all the way to the left too, only just slightly better than normal human memory. Hyperthymesia people can recall memories of the past at a much greater level than normal people. As great as this level of remembering is, it is still a long way from perfect memory.

On the right side of the scale of forgetfulness, is computer memory. In this diagram, computer memory is almost perfect. In the computer world, 100% perfect memory is an accepted standard. Can you imagine the consequences of a dropped bit in a bit-coin for example? Perfect memory is attainable and expected in computers. Like computers, all people have perfect memory. It is only our limited ability to recall that makes it appear as though our memory is flawed. All humans have super memory. As humans we are endowed with super memory, we forget nothing. We may not be able to recall everything, but it is there in our memory.

5. The Relationship Between Memory, Space, and Time

5.1. The Outside World Is Created within the Mind

The human awareness system is a marvel of biological engineering, enabling us to perceive and interpret the external world with remarkable accuracy and depth. Central to this process is the mind, the part of the brain responsible for processing sensory information. While we often take for granted the seamless nature of vision, it is a complex construct formed within the confines of the brain. First, the mind creates an internal representation of the outside world. Second, we realize this internal representation is our outside world. It is important to note that our internal representation of the outside world exists completely within the mind's memory.

The realization that the outside world is "built" within the mind raises profound philosophical questions about the nature of reality. From a phenomenological perspective, what we perceive as reality is not a direct apprehension of the external world but a neural simulation constructed by the brain. This aligns with Immanuel Kant's assertion that we experience the world not as it is but as it appears to us through the lens of human cognition.

Moreover, the subjective nature of vision is evident in phenomena such as optical illusions and hallucinations, where the brain's interpretation diverges from objective reality. These occurrences highlight the brain's role as an active creator of experience rather than a passive observer. Thus, an outside world built within the mind serves as our external, physical world.

The mind is not merely a passive recipient of sensory information but an active architect of the outside world. Through intricate neural mechanisms, processing, and memory, it constructs the external environment within the mind. This internal model, while grounded in sensory input, is profoundly influenced by cognitive factors and shaped by the brain's inherent plasticity. By understanding the mind's role in building our outside world internally, we gain deeper insight into how the outside world is built and perceived.

5.2. Is the Mind's Internal Model of Reality Already in Memory?

The question of whether the mind's internal representation of the outside world is already in memory touches on fundamental aspects of cognition, perception, and consciousness. The mind's internal representation of the outside world is a construct - a 3D model created by the brain. This 3D model is what we experience as our surrounding environment. Perception is an active process that combines sensory input with stored memories to create a coherent internal representation. This process is neither purely sensory nor purely mnemonic but rather an integration of the two. This interplay between perception and memory suggests that the mind's representation is continually updated and refined using existing memory structures.

The question of whether the mind's internal representation of the outside world is already in memory also raises philosophical considerations. If memory serves as the foundation for internal representations, it implies that perception is inherently subjective, shaped by individual experiences and biases. This aligns with constructivist theories of perception, which argue that reality is not directly apprehended but is instead constructed by the mind.

The mind's internal representation of the outside world is held within memory. Perception, memory, and cognition work in concert to create a seamless and adaptive model of reality. It is the "model of reality" that we experience as our surrounding environment. Our "model of reality" is held completely within memory at the moment we experience it.

5.3. The Mind Holds its Environment in Memory

The assertion that the human mind holds its environment in memory finds validation through scientific research and philosophical inquiry. This section explains how the mind absorbs, encodes, and stores its surroundings. The discussion draws upon key concepts in neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy, providing evidence to substantiate the claim.

The brain's ability to absorb its environment into memory is fundamentally supported by neural mechanisms, particularly those associated with the hippocampus. This structure is central to spatial memory. O'Keefe and Nadel (1978) introduced the concept of the hippocampus as a "cognitive map," demonstrating that this brain region encodes spatial relationships and landmarks within an environment. Experiments on rodents have shown that hippocampal place cells activate in response to specific locations, creating a neural representation of the surroundings. Similar mechanisms have been observed in humans, where functional imaging studies reveal hippocampal activation during navigation tasks (Ekstrom et al., 2003). These findings underscore the brain's capacity to hold its external world in memory.

The philosophical perspective further validates the claim by exploring the mind's interaction with its environment. Embodied cognition theory posits that cognitive processes are deeply influenced by the body's interactions with the physical world (Clark, 1997). This perspective suggests that memory is not merely an abstract function but is grounded in sensory and environmental experiences. Merleau-Ponty (1945) argued that perception of the outside world and memory are intertwined. The mind, in this view, is not separate from its environment. The mind actively integrates its surrounding environment into its cognitive map of the present moment.

The ability of the mind to hold its environment in memory has implications for afterlife. The illustration below shows the consensus, pre-theory concept of the mind and its surrounding environment. In this concept, the mind and its environment are two separate entities. Most people regard their surrounding environment to be on the outside of their minds. They see their mind, consisting of thoughts and emotions, as being on the inside. They see their surrounding environment to be on the outside. They are two, separate and unrelated things. If we draw up a diagram of this concept, it looks like this:

Now we can take a look at the post-theory concept of the mind and environment. Thanks to the work of the scientists above, we now know that memory and environment are intertwined. To push their conclusions are step further, we can envision the mind being three-dimensional and able to absorb the environment as it unfolds. Here we show a view of the mind as a three-dimensional space, being of the same physical size as the environment. In this view, everything that makes up the environment, including physical space, thoughts, and emotions resides in the mind. Nothing exists outside the mind. Everything exists inside the mind. The all-encompassing mind reality is realized within memory. From there it moves into long-term memory where it is retained indefinitely.

The mind's ability to hold its environment in memory is a cornerstone of human cognition, supported by neural mechanisms, contextual associations, and philosophical insights. By absorbing, encoding, and saving the environment, the brain enables navigation, learning, and adaptation, underscoring its evolutionary importance. It also allows us to internalize the exterior world, bringing it inside the mind where it is realized. The ability to take in and store space leads to a revolutionary concept: that memory is space. These two things - the mind and surrounding space, formally thought of as separate - are one. We need to leave behind the idea that our memory is a copy of the outside world. The proper way to look at is that memory IS the outside world. When we first encountered our environment, it was already in the mind as a computer model. That model was never copied as we moved on in time to the next moment. That model was retained, not copied. What exists in memory is the past moment, as experienced the first time.

5.4. Could We Be Presented with Super Memory at the Last Moment of Life?

The concept of a "super memory" emerging at the end of life is both scientifically intriguing and technologically sound. Computers don't forget. This idea prompts us to explore whether the human brain could experience extraordinary memory recall during its final moment.

One of the most commonly cited anecdotes suggesting enhanced memory at the end of life is the "life review." Individuals who have experienced near-death experiences (NDEs) often report vividly recalling significant events from their lives in rapid succession, sometimes with extraordinary clarity and emotional depth. Researchers suggest that this phenomenon could be tied to heightened brain activity during critical moments of life. Studies on dying animals have shown surges of gamma brain waves, which are associated with higher cognitive functions, such as memory and consciousness.[30] This fleeting burst of neural activity might be an all-encompassing, simultaneous recollection of life's memories.

Many philosophical traditions suggest that the end of life brings total clarity of memory. The idea of a panoramic life review aligns with accounts of gaining insight at the moment of death. Such accounts resonate with reports of life reviews. The notion of being presented with super memory at the end of life is a fascinating intersection of neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy. Theoretical evidence suggests that an all-encompassing memory recall could occur at the end of life.

5.5 Memory as Time-Space Continuum - The Kingdom of Heaven

I want to consider a computer sitting on a desk running a 3D game. As long as there is power to the computer, the game continues. The game takes place in a full environment of time and space of its making. After running the game for several hours, you reach down and select shut down. The computer goes into its shutdown routine, then the computer turns off physically. It is sitting there, inert. You could say the computer is dead.

Many people will say, look at that! I told you so. There cannot possibly be any life after death. At death, the power turns off and that's it. Death is exactly like this computer. Dust to dust, as they say.

There is, however, one important distinction that needs to be made. Both you and your friend are looking at the computer from the outside. Your point of view is as an observer of an object from the outside.

What about the view of the computer from the inside? When viewed from the perspective of being inside the computer, things change. As an outside observer, time moves on. From the inside, time stops. The information that fills the computer's memory is intact - at the moment is turned off. That's an important distinction. At the moment the computer is turned off, its memory exists. It may not exist for more than a moment, as the power drops. But for that one moment, all memory is present and accounted for. As it turns out, one moment is all we need.

In the discussions above, we have seen how the mind holds the present moment in memory as we experience it. Just like the software of the running game, we were playing a moment before. While playing, the game software exists in memory. In humans, as we play the game, our mind records the present moment, the software, and gameplay, and everything else in the computer environment. Then it retains it in long-term memory. As each moment unfolds, it is moved into memory. It does not overwrite. Each moment is retained in memory, from the beginning of life to the end. There are no dropped bits along the way.

So, from the perspective inside the computer, an entire lifetime is on the inside. On the outside, we see the computer turning off. On the inside, we are in the presence of all time we spend during life. When the mind absorbs space, as explained in section 4.3 above, it is taking three-dimensional space into memory. In that regard, memory holds the three-dimensional space of that moment. This sets up the connection between memory and space. In humans, memory contains space. Memory was space when we first experienced the moment. Memory is still space, here at the last moment. Space went into memory. That means memory is larger than physical space.

When you start taking moments as space into memory in succession, you build a continuum. The individual spaces of present moments knit together into a single four-dimensional realm. That realm is as wide as physical space and as deep in time as every moment ever experienced. This four-dimensional realm is present and accounted for at the moment the power is turned off. Once again, from the perspective of the computer being turned off, you are in the presence of an unlimited four-dimensional realm. Some call the realm the Kingdom of Heaven. It is a kingdom, physically and literally. The kingdom includes everything ever experienced, in the mind or the outside world. This only lasts a moment, as the power will soon turn off. However, for that moment you are ubiquitous within the kingdom of heaven.

Here is the amazing part. Here you are, sitting in your one moment at the end of life experiencing the kingdom of heaven. Using memory, your conscious awareness changes dimension. Yes, afterlife is only one moment in duration - to the outside world. But inside that moment, from the perspective of the person inside the kingdom of heaven, is all time. During each moment of life, memory absorbs physical space. Throughout a lifetime, memory absorbs physical time. Now at the end of life, we have a conscious awareness located at one point in space and time. However, within that one moment is all physical space and time, relative to that individual.

Thus, conscious awareness does not die. It does the opposite. It undergoes a transition becoming all space and time. We don't need anything to transpire to make this happen. We don't need to acquire anything we don't already have. We are in the presence of unlimited space and time because we capture it into memory during life. At the end of life, we hit the perfect scenario. We finally realize the entirety of our journey throughout life. We live forever surrounded by everyone we've ever known and everything we have ever experienced.

Footnotes

[1]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). A case of unusual autobiographical remembering. Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49.

[2]: LePort, A. K., et al. (2012). Behavioral and neuroanatomical investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM). Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 98(1), 78-92.

[3]: Palombo, D. J., et al. (2015). Neural correlates of autobiographical memory in individuals with and without hyperthymesia. Neuropsychologia, 65, 63-73.

[4]: Patihis, L., & Cruz, N. (2019). Highly superior autobiographical memory: Memory theory and implications for the science of memory. Memory, 27(5), 574-588.

[5]: Storm, B. C., & Jobe, T. A. (2012). A trade-off between memory and cognitive control. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(5), 899-905.

[6]: LePort, A. K., et al. (2012).

[7]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering." Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49.

[8]: Unforgettable. (2010). Directed by Eric Doe. Documentary film.

[9.]: LePort, A. K., Stark, C. E., & McGaugh, J. L. (2012). "Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory: Examination of the Structure and Function of the Brain." Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 98(1), 78-92.

[10]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering." *Neuropsychologia*, 44(12), 2189-2204.

[11]: LePort, A. K., Mattfeld, A. T., Dickinson-Anson, H., et al. (2012). "Behavioral and Neuroanatomical Investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM)." *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences*, 109(49), 20380-20385.

[12]: "The Man Who Can't Forget: A Look at Hyperthymesia." *ABC News Special Report*, 2010.

[13]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering." Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49.

[14]: McGaugh, J. L. (2013). Memory and Emotion: The Making of Lasting Memories. Columbia University Press.

[15]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering." Neuropsychologia, 44(12), 2189-2204.

[16]: Doe, J. (2008). The Woman Who Can't Forget: The Extraordinary Story of Living with the Most Remarkable Memory Known to Science - A Memoir. Free Press.

[17]: LePort, A. K., Mattfeld, A. T., Dickinson-Anson, H., et al. (2012). "Behavioral and Neuroanatomical Investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM)." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 20380-20385.

[18]: Patihis, L., & Loftus, E. F. (2016). "Memory Distortions in Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory Individuals." Memory & Cognition, 44(5), 761-774.

[19]: LePort, A. K., Stark, C. E. L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2014). "The Nature of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory: Evidence from MRI Studies." Brain and Cognition, 88, 69-77.

[20]: McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "Exceptional Memory for Autobiographical Events." Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49.

[21]: Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). "A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering." Neuropsychologia, 44(12), 2189-2204.

[22]: "The Man with the Unforgettable Memory." 60 Minutes, CBS News, 2010.

[23]: Patihis, L., & Loftus, E. F. (2016). "Memory Distortions in Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory Individuals." Memory & Cognition, 44(5), 761-774.

[24]: Price, J. & Davis, B. (2008). The Woman Who Can't Forget: The Extraordinary Story of Living with the Most Remarkable Memory Known to Science. Free Press.

[25]: Schacter, D. L. (2001). The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[26]: Seung, S. (2012). Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[27]: Cowan, N. (2010). "The Magical Mystery Four: How is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?" Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57.

[28]: Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic Memory: From Mind to Brain. Annual Review of Psychology.

[29]: Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). "The Critical Role of Retrieval Practice in Long-Term Retention." Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20-27.

[30]: Borjigin, Jimo, et al. "Surge of neurophysiological coherence and connectivity in the dying brain." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 35, 2013, pp. 14432-14437.

Bibliography

• Baddeley, Alan. "Working Memory: Theories, Models, and Controversies." Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 63, 2012, pp. 1-29.

• Bear, Mark F., et al. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. 4th ed., Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

• Borjigin, Jimo, et al. "Surge of neurophysiological coherence and connectivity in the dying brain." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 35, 2013, pp. 14432-14437.

• Clark, A. (1997). Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again. MIT Press.

• Cowan, N. (2010). "The Magical Mystery Four: How is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?" Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57.

• Ekstrom, A. D., Kahana, M. J., Caplan, J. B., Fields, T. A., Isham, E. A., Newman, E. L., & Fried, I. (2003). Cellular networks underlying human spatial navigation. Nature, 425(6954), 184-188.

• Felleman, Daniel J., and David C. Van Essen. "Distributed Hierarchical Processing in the Primate Cerebral Cortex." Cerebral Cortex, vol. 1, no. 1, 1991, pp. 1-47.

• Friston, Karl. "The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory?" Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 2, 2010, pp. 127-138.

• Gregory, Richard L. "Perceptions as Hypotheses." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, vol. 290, no. 1038, 1980, pp. 181-197.

• Hubel, David H., and Torsten N. Wiesel. "Receptive Fields of Single Neurones in the Cat's Striate Cortex." The Journal of Physiology, vol. 148, no. 3, 1959, pp. 574-591.

• Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

• LePort, A. K., Mattfeld, A. T., Dickinson-Anson, H., et al. (2012). Behavioral and neuroanatomical investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 20380-20385.

• LePort, A. K., Stark, C. E., & McGaugh, J. L. (2012). "Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory: Examination of the Structure and Function of the Brain." Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 98(1), 78-92.

• McGaugh, J. L. (2006). Exceptional memory for autobiographical events. Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49.

• McGaugh, J. L. (2013). Memory and Emotion: The Making of Lasting Memories. Columbia University Press.

• Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

• O'Keefe, J., & Nadel, L. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford University Press.

• Palombo, D. J., Alain, C., Soderlund, H., Khuu, W., & Levine, B. (2015). Neural correlates of autobiographical memory in individuals with and without hyperthymesia. Neuropsychologia, 65, 63-73. https:""doi.org"10.1016"j.neuropsychologia.2014.10.027

• Parker, E. S., Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). A case of unusual autobiographical remembering. Neurocase, 12(1), 35-49. https:""doi.org"10.1080"13554790500473680

• Pascual-Leone, Alvaro, and Amir Amedi. "The Plastic Human Brain Cortex." Annual Review of Neuroscience, vol. 28, 2005, pp. 377-401.

• Patihis, L., & Loftus, E. F. (2016). "False Memories and Hyperthymesia: Two Sides of the Memory Coin?" Psychological Science, 27(9), 1181-1191.

• Patihis, L., & Loftus, E. F. (2016). Memory distortions in Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory individuals. Memory & Cognition, 44(5), 761-774.

• Patihis, L., & Cruz, N. (2019). Highly superior autobiographical memory: Memory theory and implications for the science of memory. Memory, 27(5), 574-588. https:""doi.org"10.1080"09658211.2018.1563157

• Price, J. (2008). The Woman Who Can't Forget: The Extraordinary Story of Living with the Most Remarkable Memory Known to Science. Free Press.

• Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). "The Critical Role of Retrieval Practice in Long-Term Retention." Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20-27.

• Schacter, D. L. (2001). The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

• Schacter, Daniel L., and Donna Rose Addis. "The Cognitive Neuroscience of Constructive Memory: Remembering the Past and Imagining the Future." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 362, no. 1481, 2007, pp. 773-786.

• Seung, S. (2012). Connectome: How the Brain's Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

• Storm, B. C., & Jobe, T. A. (2012). A trade-off between memory and cognitive control. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(5), 899-905.

• The Man with the Unforgettable Memory. (2010). 60 Minutes, CBS News.

• Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory (pp. 381-403). Academic Press.

• Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic Memory: From Mind to Brain. Annual Review of Psychology.

• Unforgettable. (2010). Directed by Eric Doe. Documentary film.

• Willians, B. (2010). Interview with ABC News. "Living with an Extraordinary Memory."